FULL CIRCLE

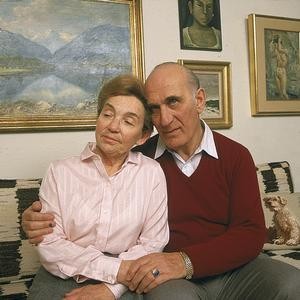

Trudy und Lewis Schloss. Lewis passed away in 2000. Trudy und Lewis Schloss. Lewis passed away in 2000.

I was born in a small industrial town in Germany, named Horst-Emscher, located halfway between Essen and Gelsenkirchen, in the Ruhr valley. Until Adolf Hitler cane to power, life for our family was relatively comfortable and uneventful. After 1933 and until "Kristallnacht" in 1933 we managed to get by and although our parents tried hard to emigrate, they were unable to get a visa to anvwhere and eventually we were "resettled" to Riga in January 1942, together with ca. 1500 other fellow-jews from our area.

When we arrived at Riga's Skirotawa Railroad station my parents and I realized at once what was in store for us and we made up our mind to do everything in our power to survive the war raging across the world. Personally, I had made up my mind to escape if at all possible. Shortly after our arrival at the Ghetto of Riga I was assigned to work at the Harbor of Riga, unloading grain from a Swedish ship. Out of the blue a Swedish sailor offered to hide me on board and take me to Sweden. It was a heavensent opportunity to leave the horrors of the Ghetto behind me, but since my escape would have meant the certain death of my parents and other hostages, I reluctantly declined this wonderful offer.

|

Still, survival and freedom was always uppermost in my mind. Somehow fate and luck was with us and my father, mother and I survived the many horrors of the Riga-Ghetto, KZ Kaiserwald, and the many different small camps. We all were reunited early August 1944 on a ship loaded with a part of the remainder of the many thousands of Jews who were starved, mistreated and killed by the German, Latvian SS and collaborators in Latvia. Our destination turned out to be the KZ Stutthof near Gdansk, (now in Poland). Stutthof was the most brutal concentration-camp we had yet been in, and when a short while later we heard we were being shipped to KZ Buchenwald, other prisoners told us: we were going to a "sanatorium".

It was at Stutthof that I last saw my poor mother, near the fence of the women's camp, for the last time. My wife Trudy told me later that she had managed to survive only to succumb to typhoid fever three weeks after the liberation by Russian troops. Late in August 1944 the freighttrain took my father and me together with many other fellow-prisoners to KZ Buchenwald. Upon our arrival the camp was so overcrowded with prisoners of every nation, we were assigned to "live" in a large tent on the campgrounds. It was there during a US bombing raid on the camp that I met a group of about 120 American, British and Canadian pilots. These had escaped their prisoner-of-war camps. But they had been caught and as punishment brought to KZ Buchenwald. It was through them that my thoughts of escape received fresh nourishment.

When I heard via the grapevine a number of prisoners were going to be sent to a satellite-camp (Aussenlager) at the "Bochumer Verein", I immediately volunteered my and my father's services. (Something I had never done before.) I knew Bochum was just ten miles from my hometown Gelsenkirchen. Luck was with us and we were selected for this transport. So early in September 1944 we and about 1000 other camp-inmates arrived at a newly built camp on the property of the warplant at the Bochumer Verein. This concentration-camp was located adjacent to the plant and surrounded by apartmenthouses on several sides. The locals could look from their windows directly into our camp and watch everything.

At the Bochum camp every prisoner had his own bunk, a new enamel dish and a spoon and fork. After our experiences this was the hight of luxury. My dad and I were ordered to share the operation of a very large overhead crane in the main factory hall. We each worked 12 hour shifts. The work location was great for we were operating ca. 50 feet above the SS, our fellow-prisoners and the local German foremen who supervised the production of the prisoners. My father and I had what one might call "delicious privacy".

However our idyll did not last very long because soon we had to endure heavy airraids and finally one particular raid heavily damaged the warplant and destroyed most of our camp-barracks. Although we lost a number of our fellow-inmates in this bombingraid, we welcomed every airattack for it meant the Allies were getting closer and closer. Furthermore an interesting thing happened after these heavy raids: the German civilian foremen began speaking with us. It suddenly seemed as if even the dumbest worker realized that the war was lost for Germany. My father started a conversation with an older german foreman who commented on how well versed he was in the German language and inquired as to "how he learned to speak such excellent German." When my dad told him he was born in Germany and that he had lived nearby, the German asked him his name, my father said "my name is Max Schloss" and requested his name in return. When the foreman raid: "my name is Heinrich Hoppe", my dad asked if he was perhaps related to a former friend of his, named "Fritz Hoppe". Heinrich Hoppe, very surprised, answered "That was my late brother", whom my father had known to be an old Social-Democrat. Both had an animated discussion regarding the past as well as the present and at the end of their conversation, Heinrich Hoppe gave my dad his sandwich. This was a gift my father gratefully accepted. Later in the barracks, when we discussed the events of this day, we began to think about how we might use Heinrich Hoppe to make contact with the outside world.

Before our deportation to Riga, my father had left for safekeeping certain family papers with an old friend, a devoutly religious man by the name of Heinrich WILMES. We decided to ask Heinrich HOPPE to contact Heinrich WILMES and to ask him to supply us with extra food to supplement our meager rations. Heinrich Hoppe agreed to our plan and the very next Sunday rode his bycicle to the home of

Heinrich Wilmes. Heinrich Hoppe had a hard time convincing Heinrich Wilmes that we were in a concentration-camp near his home as well as of his personal reliability. But finally he gave Heinrich Hoppe a food package for us and for himself as well because he he still felt unsure of Heinrich Hoppe's legitimacy. Of course, Heinrich Hoppe gave us the gift. The contents of bread sausage, butter and cookies were a thrill for us to see and mad e us a fantastic gourmet meal. After the initial visit, Heinrich Hoppe made this trip nearly every Sunday and the giftpackages did a great deal to keep us in better physical shape than the rest of our comrades.

Meanwhile I kept thinking of how to escape. I spent much time on the roof of the plant during every airraid, disregarding the danger of shrapnel or bombs, trying to discover a weak spot in the system, anything to enable us to flee. To my chagrin I found the gates heavily guarded during every raid and I nearly despaired of ever getting out. Then, just before Christmas 1944 Heinrich Hoone told us that Heinrich Wilmes had said "he would welcome our visit to his home". We were elated, for HEINRICH WILMES knew our present condition and he meant for us to have a refuge should we be able to find a way to escape. NOW my efforts to attempt and prepare for our flight started in earnest.

In order to get out we needed a number of things: First we had to have civilian clothes and also a pass which the civilian workers used to enter and leave the guarded camp and works. And most important, the knowledge of how to flee. So our friend Heinrich Hoope began bringing in old clothing which we hid in the cabin of the spare crane. And then we needed to forge two gate passes. Heinrich Hoppe supplied us with 2 blank postcards equal to the size of the pass plus a black and a red pencil. During the lunchperiod he would hand me his pass and I used my limited artistic skills to make 2 usable copies. There was however a MAJOR problem: the passes needed an automat-size ID photo. The SS certainly could not be counted upon to provide this service, so now WHAT?

Well here probably comes the most incredible part of this story. Ever since my very early days in the Ghetto and thru all the other camps I carried a small, square "LIMA" tin candy can which held things like a razor blade, a few German coins, needle and some thread, a few buttons, etc. etc.. Yet it did not contain a single photo of either my mother, my sisters or any other relative, to remember them by, but one photo each of my father and of myself. Why I did this I am at a loss to explain, but these were the Photos I now needed for the forged passes.

Soon over two months had passed since Heinrich WILMES offer of santuary and rumors were flying around that we were going back to Buchenwald. Time was of the essences having the clothing, the passes and still not knowing how to get out frustrated me no end. I continued my vigil during airraids, day or night, always to observe double and often triple guards posted at the gates. The fences of course were electrified and offered no way of escape. Then on the morning of March 14, 1945 after the all-clear had sounded, I went up to the roof which was about 10 feet above our crane and I noticed to my surprise only a single guard on duty. Right then and there I decided this was THE DAY.

I went to look for my father and convinced him to go with me even though he was quite ill. We proceeded to climb the steel ladder up to our crane cabin and changed into the hidden civilian clothes. I put on my father's eyeglasses and barely able to see, we went down the ladder, in full view of everybody, walked out of the large factory hall, then the 200 yards to the gate, unchallenged and unrecognized by anyone. We nervously talked to each other in German and when we reached the sole SS guard at the inner gate, he just said: "why are vou talking so loud" and with barely a glance at our forged passes let us out. The same thing happened at the works gate and at the local police control. It was about 2:30 in the afternoon, the sky was blue, the sun was shining and we were FREE as well, at least we were out of the concentration-camp.

We began walking in the general direction of Heinrich Wilmes' house, when I decided to put my few German coins to use by hopping unto a passing streetcar, which took us about a mile or so, when another airraid forced everybody off into a nearby shelter. We decided after the all-clear not to take any chances and to continue walking towards Heinrich's house which we reached after dark. He had a difficult time recognizing us but after a few long moments welcomed us inside. He put all kinds a food on the table and was absolutely amazed at the amount of food we devoured. We stayed with Heinrich Wilmes for about two weeks "hidden in the open", he just declared us to be bombed-out relatives. However, during another airraid we went with him to a nearby shelter where we were recognized by a policeman who used to live just one block from our former home. Fortunately he did neither arrest nor denounce us. But we agreed it was time to move on to our next hidingplace. This vie found at Heinrich* s brother Theo Wilmes in Essen, where we remained until our liberation on April 10,1945. We were liberated by infantrymen of the 507th Para. Infantry Regiment of the 17th Airborne Division. Thus we were freed near the starting point of our journey into darkness. We had survived. We had come full circle.

P.S. I offerred my services as an interpreter to the 507th Provost marshall, was accepted and put into U.S. Army uniform the very next day. That without any proof of identity or papers, ft could only happen with Americans: thank the Lord for them.

I spent the next year serving various US Army outfits and at the U.S. Consulate at Frankfurt, until my wife Trudy and I left for the U.SoA. We boarded the very first ship, the "Marine Flasher", loaded with displaced persons early May 1946. My father lived in Essen and served at the denazifacation office until he could join us in the New World in January 1947. He never completely regained his health and passed away much too young, barely 65 years old.

Heinrich Hoope continued to live in Wattenscheid, Germany and passed on in l965. Theo Wilmes still lives in Essen in poor health. He is now 87 years old and still has his wife to take care of him. Our friend Heinrich Wilmes is now 89 years old and physically healthy, but has become a bit forgetful. Whenever we are in Germany we do not fail to see him and his family for without his help and generosity we probably would not have survived. About 14 years ago, both Heinrich and Theo were awarded a certificate of honor by Yad Vashem in Jerusalem.

By Lewis R. Schloss. Source: Archiv Gelsenzentrum e.V.

Andreas Jordan, Februar 2011 | ↑ Top |

|